History of Pittsburgh MMA Mixed Martial Arts

If you want to know how mixed martial arts and MMA was cultivated in Pittsburgh, here is the real story and history…

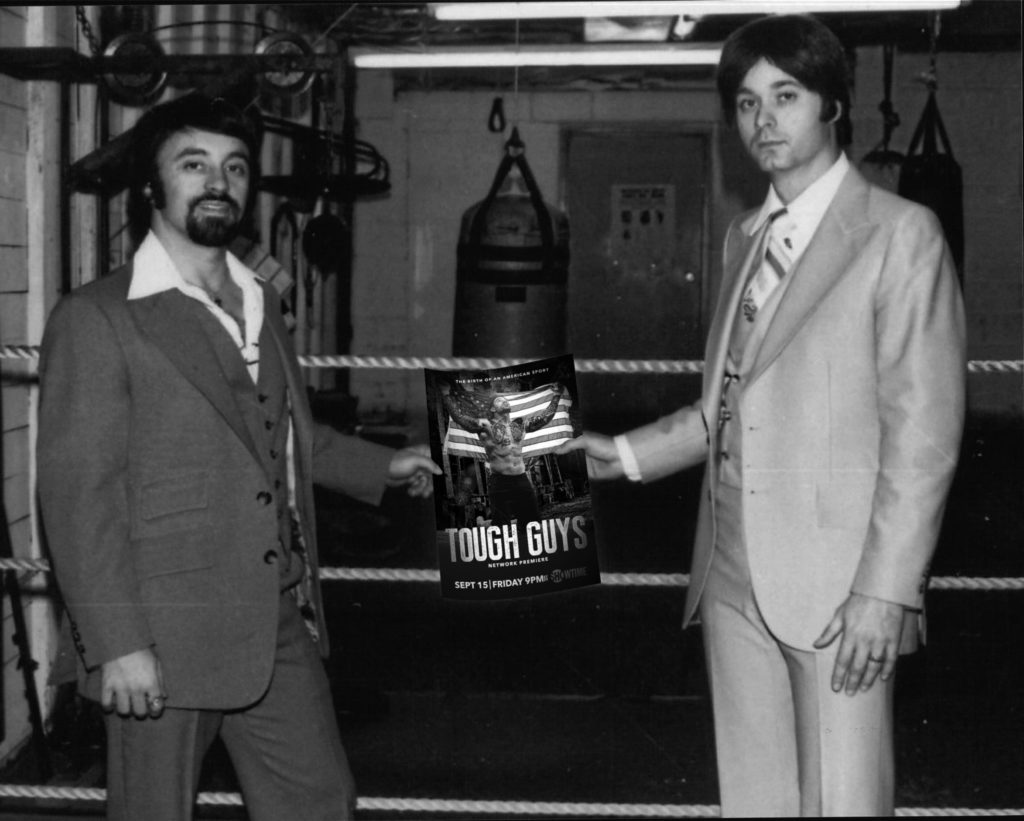

Excerpt used with permission from Tough Guys ©

Long and Winding Road

“Different roads sometimes lead to the same castle.”

-George R.R. Martin

Caliguri and Viola agree, Pittsburgh felt the ripple effect of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, but MMA had been brewing since the 1970s. Viola explains, “Formal mixed martial arts instruction began to gain ground shortly after we were ostracized in the early 1980s, and Don Garon was instrumental in carrying the torch.”

Garon, an Okinawan Kenpo stylist, earned a reputation as a skilled fighter, battling Pennsylvania legends such as Billy Blanks on the karate circuit. Before Tae Bo became a novelty, Blanks was a true world karate champion and even fought as a kick boxer for CV Productions before he settled on the West Coast.

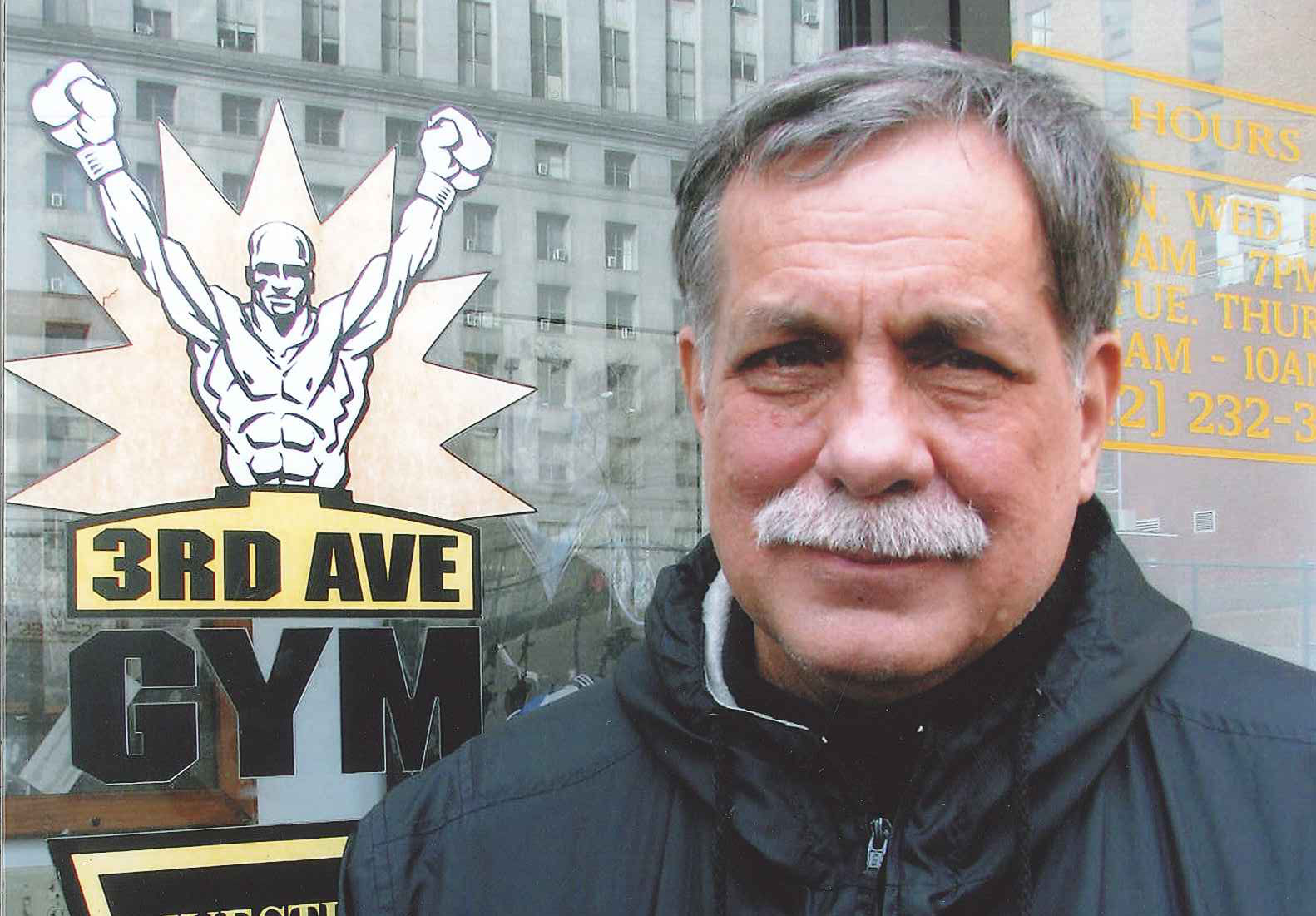

Viola recalls meeting Garon in the years leading up to the Tough Guy competition. “I remember stopping by Mike Donovan’s Kenpo school in Monroeville with Keith Bertiluzzi in the early 70s. In those days, I kept an ear to the ground about any new schools in the area. Don was working out there, but all that I really remember was a huge Doberman pinscher snarling and guarding the dojo door. All kidding aside, Don was a great marital artist and a great friend to Frank and me. His heart was as big as his skills.” By the mid 80s Garon began training with Dan Inosanto, a direct student of Bruce Lee and the authority on Jeet Kune Do. He also became an avid proponent of submission wrestling and sought specialized training from Erik Paulson, hosting clinics and seminars that broadened the views of many local fighters. Paulson, who has reportedly learned from nearly forty different experts, masters and instructors over his career, was a quintessential mixed martial artist. (Among his notable instructors was Rorion Gracie.) Paulson would go on to be an MMA champion and his influence is still heavily felt in Pittsburgh. The Garon-Paulson connection would set the stage for Pittsburgh’s new MMA establishment.

The state may have put the brakes on MMA as an organized sport, but the region continued mixing martial arts and a swarm of Pittsburgh fighters kept the spirit alive.

William “Sarge” Edwards was part of the Don Garon clique, but had a unique identity all of his own. He was a multi-discipline Guru, possessing a mixed martial arts mindset that incorporated karate, boxing, and Jeet Kune Do. Caliguri remembers, “Edwards was always eager to fight on our kickboxing cards. He taught outside the traditional standards of most conventional schools.” He built a following of reality fighters who shied away from a traditional atmosphere. Edwards was revered for his ability to equate hand to hand combat into sport specific training; especially the x’s and o’s of football. His close quarter strikes, signature techniques of Jeet Kune Do, morphed into an innovative training method known around NFL circle’s as the “Tunch Punch” (made famous by Pittsburgh Steeler Pro Bowl offensive lineman, Tunch Ilkin). Ilkin and teammate Craig Wolfley studied under Sarge and continue to carry on his legacy today through their coaching.

Viola explains, “There were a lot of great potential mixed martial arts competitors in the early days. Curtis Smith was one. He was a highly recruited athlete by the University of Pittsburgh and played fullback for the Panthers (blocking for the legendary NFL Hall of Famer Tony Dorset). Curtis was a champion wrestler and martial artist (well versed in Japanese jujitsu and karate) He had all the tools.”

Smith shared his cross-training methods with the Pitt student base. His talents landed him a full time position at the University to instruct martial arts as an accredited course in 1981. He also joined the University of Pittsburgh City police force (now a 35-year veteran) and serves as a special tactical self-defense instructor for the State of Pennsylvania, national police organizations, and other international law enforcement agencies.

Smith recalls, “There was no bigger influence on me than Master ‘Flew.‘” Theodore Flewellen was a true ambassador of combat, amassing a lifetime of hands on experience dating back to 1936 when he first began teaching the art in Pittsburgh. In 1972 Smith became his prodigy, “I took lessons for a $1.00 a class at the Kingsley House and I never looked back. He was a Lieutenant in the Sheriff’s Office, and he single handedly shaped the way the force looked at hand to hand combat.” In 1980, the Allegheny County Police Academy instituted the Eugene Coon & Ted Flewellen Award, an honor bestowed upon Smith for his superior physical fitness skills.

Viola adds, “Curtis would have been a great candidate to join our pro league. He was big, strong, agile, and could fight on the ground. He was in his prime during the early 1980s, so a potential match up with someone like Rorion [Gracie] would have been very interesting if we continued. It’s just another, what if.”

Countless other men and women have forged the way for an MMA mentality in Western PA, most testing their skills at open martial arts competitions hosted by CV over the years.

In the wake of UFC, submission wrestling and freestyle jiu-jitsu made an impact on the Pittsburgh area before Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. Eric Hibler and Dan Moore stood on the frontline of the grappling scene; men on separate paths but fortunate to share a common influence: Don Garon.

Hibler remembers, “Don opened everyone’s eyes by bringing in experts in submissions, JKD [Jeet Kune Do] and Philipino martial arts.” Hibler and Moore were always thinking outside the box, and soon gravitated towards more of a no-holds-barred approach; a new regime led by Sarge Edwards. The standouts got the itch to pursue submission wrestling and MMA would take their passions to the next level.

Moore began teaching Kenpo karate in 1982 with the establishment of Penn Hills Martial Arts Center. Slowly he transformed his system into a strictly MMA school by the early 1990s. His curriculum began to incorporate elements of Eric Paulson’s combat submission wrestling and Larry Hartsell’s Jun Fan Grappling. “I simply advertised ‘We’ll teach you to fight’ to get away from attracting kids. We were teaching JKD [jeet kune do] and shoot wrestling and I wanted an adult clientele.” Soon Moore was producing pro fighters like Jermey “Bioharzard” Bennet, one of the first men from Pittsburgh to ever set foot inside a cage.

The ambitious “Hib,” as he became known abound the ‘Burgh, opened the first full-scale “big-time” facility that catered to modern MMA enthusiasts. Hibler founded Practical Fighting Concepts in early 1990s which later became known as Pittsburgh Fight Club by 2006. His emphasis was simply “cage fighting” and he had all the amenities; a full-sized octagon cage, regulation boxing ring, raised jiu-jitsu mats, and a forest of heavy bags.

The men and women who trained there gained a reputation as “Pit-fighters,” a place where local pedigrees [pros] like Chris Custer and Dave Sachs made names for themselves. One of Hibler’s protégés, Don Kaecher, would amass a pro fight record of 9-1; his only defeat to UFC veteran Hermes Franca early in his career. In keeping with the NFL/MMA tradition in Pittsburgh, Kaecher recently [spring 2012] gave Steeler all-pro Linebacker LaMarr Woodley private instruction in mixed martial arts during the offseason. Kaecher explains, “Bill [Viola Jr.] introduced me to LaMarr, and we immediately got to work.” The Viola’s believe, “That martial arts can benefit pro athletes in every sport.”

Next to join the submission wrestling subculture was Ed Vincent who trained extensively under Walt Bayless in Utah. Vincent recalls, “I actually got my start in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. I trained for nearly a year with Pedro Sauer, but the commute was over an hour away from home and I discovered the Bayless school was just 5 minutes away.” Vincent would earn a black belt in freestyle Jiu-Jitsu and bring that knowledge back to Pittsburgh in the late 1990s.

It wasn’t long before he built a dedicated following, attracting high profile students that included the before mentioned Pittsburgh Steeler Craig Wolfley (an early student of Sarge Edwards). Vincent remembers, “Walt [Bayless] taught more like a wrestling coach, and we crossed over to gi and no-gi (submission grappling). I brought that style of teaching to the area and people took to it. The name “Freestyle Jiu-jitsu” was just a way to emphasize the no-gi aspect of the art. When people saw Gracie and Shamrock use submission skills, they were amazed and wanted to learn how to fight on the ground too.”

While visiting his family back home in Pennsylvania, Vincent entered and won the light heavyweight advanced division at Pittsburgh’s first-ever submission grappling championship hosted by CV’s Frank Caliguri in 1997. It was a who’s who gathering of local ground-game pioneers including Chris Custer, Don Kaecher, and heavyweight champion, Dan Rae (co-founder the CFC–Complete Fighters Club).

Rae along with Pat Ramsey opened the first mixed martial arts club in Westmoreland County (a Pittsburgh Suburban area) in 1995. To accommodate their large student base, Rae and Ramsey eventually moved the class from Larimer, Pennsylvania to Viola’s Allegheny Shotokan Karate Club in 1997. Rae had built an early rapport with the dojo where his daughter Leah, was a student.

“In the early days, very few people were training in mixed martial arts, so if you heard of a talented fighter, you paid him a visit. I remember leaving [Doug] Selchan’s dojo bruised and bloody and loving every minute of it.” Selchan won the Gold medal at 1999 Pan American Games; 80+ Kilo Kumite. Former UFC Champion Lyoto Machida would make that style of traditional Kumite famous in MMA circles years later. (Incidentally Selchan began his training at Allegheny Shotokan under Viola).

Another tie between the Pittsburgh MMA community and Viola’s dojo was CFC’s Ramsey, who had trained at Allegheny Shotokan in the late 1970s, crossing paths with MMA pioneer Dave Jones, an alumnus of CV fights. As Viola describes it, “The degree of separation in mixed martial arts in Pittsburgh is very thin.”

As the decade progressed, a pair of pugilists kept Pittsburgh in the limelight as former world heavyweight champion Michael Moorer

defeated Evander Holyfield to win the Lineal/WBA/IBF World Heavy Weight Titles in 1994, and later Paul Spadafora would secure the IBF World Lightweight Championship in 1999. Kurt Angle kept Pittsburgh’s wrestling tradition alive by winning the Gold Medal (heavyweight freestyle wrestling) at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

It wasn’t long before the UFC would call, trying to entice Angle into the Octagon in 1997. Angle explains, “I was offered a 10-fight deal at $15,000 per match. I was intrigued, but instead opted for a contract with the WWE in 1998 and an opportunity at the big money.

Angle would go onto become one of most famous pro wrestlers of the era; the first and only 12 time World Heavyweight Champion in professional history to hold all TNA and WWE top titles. In 2006 rumors began to circulate that Angle wanted to make a bid in the UFC when he left WWE. “I started to look at the prospect of MMA very seriously in 2006,” says Angle. “I worked out at Greg Jackson’s Camp for three months, but it was difficult to arrange with my schedule. I found a perfect fit in my backyard, and began extensive training at the Pittsburgh Fight Club with Eric Hibler. Hib was a great coach and he prepared me to fight anyone.”

Angle continues, “I had just signed with TNA and Dixie Carter (Total Nonstop Action) and Dana [White] approached me with a very lucrative offer. I was ready to make a move into mixed martial arts, but at the same time I couldn’t just leave TNA hanging. I wanted to do both. Dana gave me an ultimatum: quit pro-wrestling. We couldn’t come to terms.”

In an Antonio Inoki-promoted pro wrestling match, Angle defeated Brock Lesnar (later UFC’s heavyweight world champion) by submission in 2007 and then challenged him to a real MMA fight. “In my opinion, Brock is one of the baddest dudes on the planet, and if I’m going to fight, I want to fight the best. Randy [Couture] is another phenomenal fighter. I would have fought either one of them. Even though they had great wrestling backgrounds, I felt my skills were that much better.”

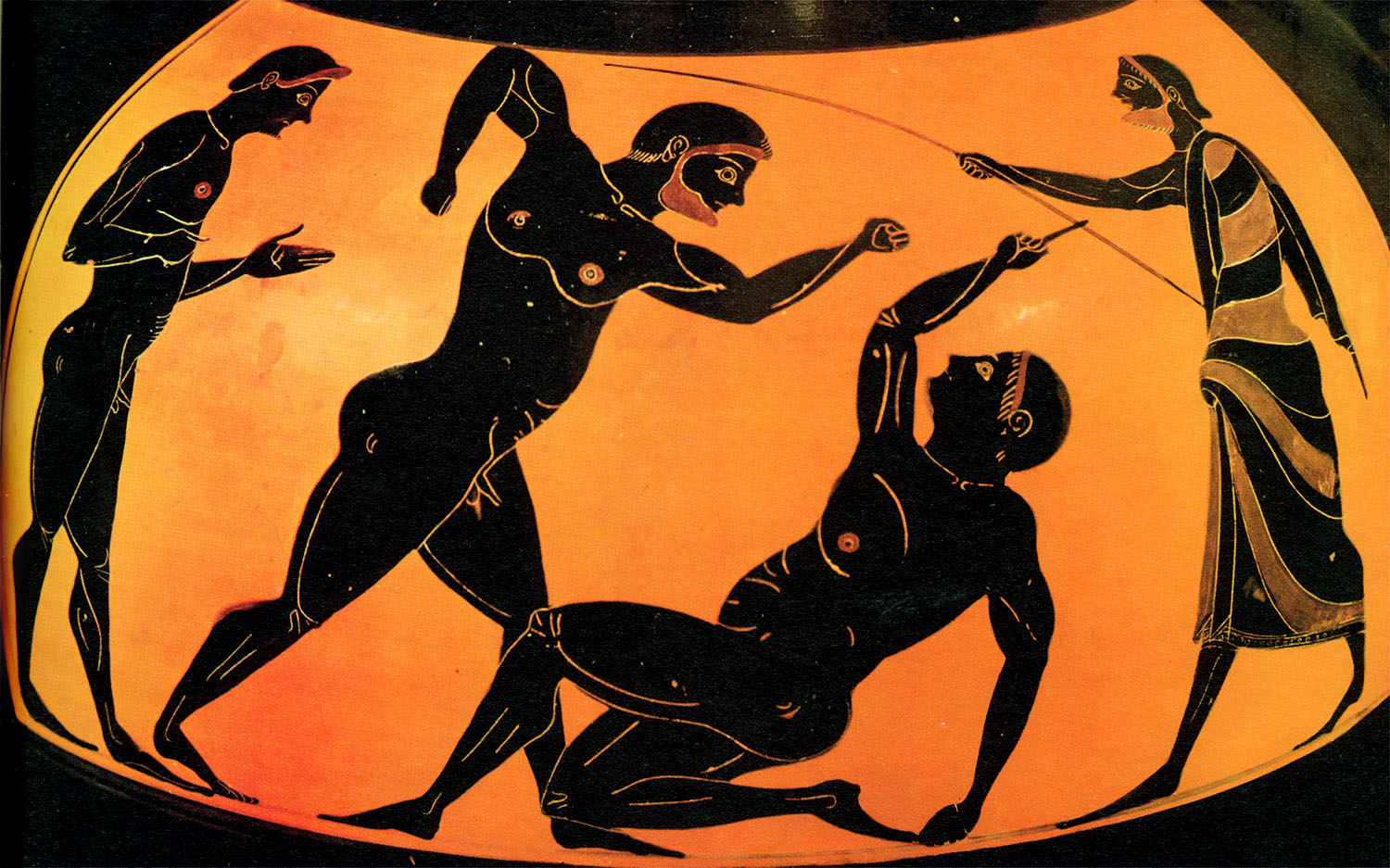

Bad blood had actually been brewing between Inoki and Pittsburgh pro-wrestling stars since the early ‘70s when the up-and-coming Japanese fighter reportedly tried to make a name for himself by attempting a real submission on Bruno Sammartino. The alleged plan to turn the bout into a “shoot” or a real match was supposedly drawn up by Karl Gotch (who taught Inoki authentic submissions), but the stronger American champ is said to have brushed off the attempt, instead punishing him with a barrage of real beatings. Inoki fled the ring and let his tag team partner finish the match in its classic predetermined or “worked” fashion.

Inoki was the most famous of Karl Gotch’s protégés, pro-wrestlers who mastered the art of hooking and shooting. Inoki founded New Japan Pro Wrestling, an organization that would straddle the line between fake and “strong style” or more realistic wrestling matches. The promotions ultimately created a breeding ground for future mixed martial artists and were a precursor to shoot-wrestling tournaments and later Shooto. Erik Paulson would become the first American to win the World Light Heavy Weight Shooto Title, valuable experience he would share with his Pittsburgh students.

However, pro wrestling and submission wrestling would have to make room for the next grappling trend in Pittsburgh: BJJ. Brazilian jiu-jitsu, although widely popular, didn’t really impact the Pittsburgh area until early the 2000s. Viola’s son, Bill, Jr. hosted the region’s first Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournament in Pennsylvania in 2003. The annual championship, (now the longest running Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu event in Pennsylvania) is now a mainstay at the Kumite Classic, Pittsburgh’s Mecca for martial arts. Steel City Martial Arts won the team honor at that first competition. Viola, Jr. recalls, “The coach of Steel City was Sonny Achille. He had a very talented group of BJJ competitors and they made their presence felt. It was the first tournament of its kind in Pittsburgh, so all the schools were represented.

“I hadn’t met Sonny before, but he knew my father from the Laurel State Karate Championships (Viola Senior’s tournament). There really isn’t anyone in Pittsburgh who didn’t cut their teeth at my dad’s and Frank’s tournaments.” In the 1970s, Achille began his marital arts journey learning Judo under the tutelage of Nick Zaffuto. Decades later he would become Pittsburgh’s authority on Gracie Jiu-jitsu training under Pedro Sauer (a direct student of Heilo and Rickson Gracie). After making the commute to Utah for nearly 10 years, Achille became the first Pittsburgher recognized in the Gracie lineage as a legitimate black belt in 2009.

In the early 2000s, America was in the midst of a martial arts revolution and cross-training proved to be the most effective way to learn. Viola explains, “For some of us, it was old hat. BJJ added a new element, but the concept of combined fighting, as we liked to call back in the 1970s, was common. You just continue to adapt and add new techniques to your curriculum. If we have learned anything over the years, you have to understand that all martial arts have pros and cons. I often laugh when new kids on the block brag about teaching MMA and try to degrade all other arts. These guys didn’t even come onto the scene until after they saw it on TV. But make no mistake; some of us were around long before the UFC and can appreciate the past, present and future of reality fighting.” Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and grappling were hot, but Mixed Martial Arts still had a narrow audience. The UFC had as many haters as supporters, and the sport struggled to find its true identity. Read more

When Marshal Carper broke up with his long-time girlfriend, he packed up his white belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and moved from rural Pennsylvania to Hilo, Hawaii to train at the BJ Penn MMA Academy.

When Marshal Carper broke up with his long-time girlfriend, he packed up his white belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and moved from rural Pennsylvania to Hilo, Hawaii to train at the BJ Penn MMA Academy.