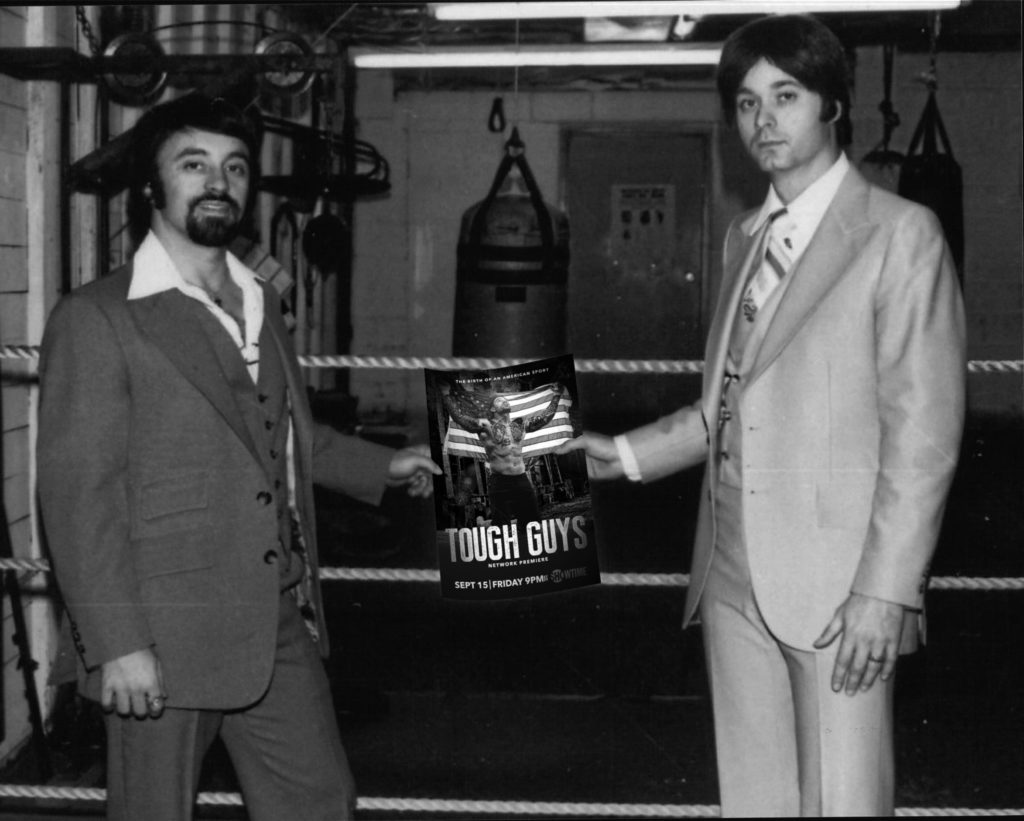

The December 2011 issue of Playboy Magazine makes mention of CV Production”s “Tough Guy” matches circa 1980. The Pittsburgh based MMA fights are the untold story of Mixed Martial Art”s early development as a mainstream sport. Bill Viola and Frank Caliguri are now receiving credit for a sport that they laid the groundwork for in 1979. To truly comprehend how organized and ahead of their time the “Tough Guy” competitions were, please read

The sport, though not officially organized until 1993 (until then it was little evolved from the unregulated “tough guy” matches of an earlier era)

Author Steve Oney Photographer Matthias Clamer

On a hot summer afternoon, Herschel Walker, wearing a Best Damn Sports Show T-shirt and Clinch board shorts, strides into the 2,500-square-foot main room of the American Kickboxing Academy in San Jose, California. At six-foot-one and 219 pounds, he is, in a word even his friends use to describe him, a freak—a magnificent physical anomaly. Walker’s trapezius muscles flare above his shoulders like the wings of an avenging angel—one who happens to have a 21-inch neck, a 48-inch chest and just 2.4 percent body fat. His 33-inch waist, the result of the 3,500 sit-ups he has done each day since he was a teenager, is essentially nonexistent, a mere transition to his 25-inch thighs. Open-faced and handsome with an easy smile, strong nose and tiny ears set far back, Walker appears to be ageless. That, however, is not so. In a few months he will turn 50.

Between 12 and two every Monday through Friday, the red tatami-mat-textured floor of the kickboxing academy is the scene of a mixed martial arts workout that Walker, who knows something about the subject (1,000 push-ups have also long been part of his daily regimen), calls “without a doubt the hardest training I’ve ever done.” MMA demands excellence in half a dozen disciplines—among them boxing, wrestling, jujitsu, judo and Muay Thai boxing. The sport likewise requires absolute cardiovascular fitness, and sessions conclude with set after set of sprints and bear crawls. First and foremost, however, it is about fighting, and fighting is what this temple to MMA stresses above all else.

As Walker squares off against a light heavyweight named Kyle Kingsbury, he is surrounded by the best of the best. In one corner Cain Velasquez, MMA’s premier heavyweight, grapples with up-and-comer Mark Ellis, a 2009 NCAA Division I wrestling champion. In another corner Josh Thomson, a standout MMA lightweight, rolls with the highly ranked Josh Koscheck. Elsewhere Daniel Cormier, an erstwhile Olympic wrestler, and Luke Rockhold, a vaunted contender, practice holds and parry blows. In this arena the most dangerous fighters in the world regularly butt heads.

Walker, the former tailback who led the University of Georgia to the NCAA football championship in 1980, won the Heisman Trophy and went on to a storied 15-year pro career (mostly with the Dallas Cowboys), first walked into the American Kickboxing Academy just two years ago. “He came to the gym very accomplished in other areas,” says Bob Cook, who has trained Walker from the start and stands at the edge of the room, watching him work. “But he had a beginner’s attitude. He got here early, stayed late and mopped the floors afterward. Never has there been a time he has taken the easy route. If we run sprints, box five rounds and wrestle 30 minutes, he never opts out. Some people come in and say, ‘Don’t punch me in the face.’ Herschel came in with a fighter’s attitude. He’s been punched plenty in the face.”

“I’d rate Herschel today at a midrange pro level, and that’s a high compliment,” adds AKA founder and proprietor Javier Mendez, who kneels alongside Cook. “He’s the strongest man I’ve ever worked with, and his striking and grappling were always good. But his wrestling and jujitsu are now at another level. He’s worked hard to learn them.”

Walker has also worked hard to dispel doubts expressed by some in the MMA hierarchy. The sport, though not officially organized until 1993 (until then it was little evolved from the unregulated “tough guy” matches of an earlier era) and not sanctioned by a state athletic board until 2000, has quickly developed a fierce, well-informed following and a proud lore. Dana White, president of Ultimate Fighting Championship, MMA’s top promotion company, scoffed, “He’s too old for football but thinks he’s young enough to fight? Fighting is a young man’s sport. You need speed, agility and explosiveness—all that goes with age.” For Walker, such cracks, in a friend’s words, “were like lighter fluid.”

In his professional MMA debut in 2010, Walker defeated the relatively untested Greg Nagy in three rounds by a technical knockout. In January 2011, against the far tougher Scott Carson, who boasted a 4–1 record and who is a protégé of UFC stalwart Chuck Liddell, Walker scored a more impressive victory. After absorbing a vicious kick to the face in the contest’s opening seconds, he took Carson to the ground with a ferocious left and then pummeled him with a flurry of knees to the ribs and punches to the head that caused the referee to call the contest before the first round had concluded.

Skeptics still abound, pointing out that Walker’s fighting style is basic and safe. “He’s not the alpha male yet,” says one. “He’s about controlling the opponent and staying out of trouble.” Still, those who have followed his progress believe he is becoming an undeniable force. “It’s crazy to see how good he’s gotten,” says Velasquez, who bested the formidable Brock Lesnar in 2010 to win the UFC’s heavyweight belt. Although 20 years younger than Walker, Velasquez has functioned as the older man’s mentor, teaching him how to plot strategy and avoid the brutal knee and arm bars that can prompt even the greatest to submit, or tap out. “He’s picked up the game fast. He just has to keep building.”

Now, in the stultifying steam bath that is July in central California, Walker is preparing for a third fight. His opponent has yet to be named, but the unanimous opinion is that the match will present a huge step up in difficulty. “They’ll pick somebody tough,” says Mendez. “They’ll elevate the level of competition. He’s going to face someone much more experienced than the last guy. It’s going to take Herschel being here every day for three months to get ready, but once he makes up his mind, that’s what he’ll do. He doesn’t mess around.”

Even so, Walker acknowledges how unlikely it all is. “What am I doing in there running around with those 20-year-olds?” he asks as he emerges into the AKA lobby, sweat pouring from his face, brow furrowed. For a serious man, the soft-spoken ex–NFL star is not without a sense of absurdity. “Am I really 50? It’s weird.”

To those who have known Herschel Walker through the years, it is not surprising he has decided to plunge into a sport in which there are no pads, pain can be inflicted in a dizzying number of ways and the playing field is an unforgiving fenced enclosure known as “the cage.” Vince Dooley, Walker’s coach at the University of Georgia, recalls that on Sundays during the college football season, a day when most players were too sore from Saturday’s game to crawl out of bed, Walker would attend tae kwon do classes. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Dooley. Michael Irvin, Walker’s Dallas Cowboys teammate and now an analyst for the NFL Network, says, “When Herschel was the baddest motor scooter on earth, he’d say, ‘I want to fight Mike Tyson.’ I’d say, ‘Herschel, do you know what that guy does to people? Let’s just beat the Redskins next week.’ But he believed he could beat Tyson. MMA is par for the course for him.” Troy Aikman, the Cowboys quarterback during Walker’s final seasons in Dallas and now a broadcaster for Fox, also believes his former teammate’s latest incarnation is apt. “When Herschel decided to get into it,” he says, “an acquaintance of mine involved in MMA told me he didn’t give him a chance. I replied, ‘I’ve seen enough of this guy over the years that I wouldn’t bet against him on anything.’ He’s highly driven. He doesn’t take on anything halfheartedly. He runs a heck of a lot hotter than people realize. He’s a killer.”

Walker’s rationale for entering the world of MMA is not what many may imagine. “People think I’m doing this for the money,” he says, “but I say, ‘Guys, I don’t need the money. The businesses I’ve built since I got out of football provide a bigger payday than any fight can bring me.’ ” (Walker donated the purse from the Carson bout to his Dallas church, Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship.) Nor, he adds, is he mentally unbalanced. In 2008 Walker made news by revealing that he suffered from dissociative identity disorder—what would once have been called multiple personality disorder. In Breaking Free, his book about his battle to come to terms with the condition, he writes that in its throes he had experienced fits of murderous rage. But after years of therapy, he says the problem is now under control. “The story people want to hear is that I’m out of whack. But that’s not me. I have not become an MMA fighter because I have an anger issue.” The truth, he adds, is both simpler and more complex.

Few successful American athletes have enjoyed as varied a career as Walker has. Even as he was leading Georgia to a national football title, he was competing on the collegiate track circuit, running a 9.1-second 100-yard dash and briefly holding the world’s record in the 60-yard event. Before the start of a senior year that would almost surely have seen him break nearly every NCAA rushing mark, he became the first collegian to bolt not just to the pros but to the fledgling USFL. The New Jersey Generals (soon to be purchased by Donald Trump) signed him to a multimillion-dollar contract. When the upstart league folded after three seasons, Walker joined the NFL’s Cowboys. In Dallas he not only played football but, to prove he could, danced with the Fort Worth Ballet. In the 1992 Olympics he competed on the United States’ two-man bobsled team, finishing seventh.

As Walker sees it, MMA is simply a new challenge. “One night I was watching The Ultimate Fighter on Spike TV,” he says, “and someone said, ‘We’re the best athletes in the world.’ I thought, That’s a bold statement. I thought, I’m not trying to be arrogant, but I’ve always thought of myself as being one of the best athletes in the world. I’ve always wanted people to say, ‘Herschel Walker wasn’t just a great running back but a great athlete.’ So I said, ‘I’ll give it a shot.’ ”

Thus began Walker’s pilgrimages to San Jose, where he spent four months living in a hotel room before his first fight and six months prior to his second. This was indeed a new challenge, and for Walker challenges are not to be taken lightly. “I don’t see in between,” he says. “I see only the white and the black. You win or you lose. There’s no such thing as just playing well. You do the job or you don’t do the job. I don’t want to be just a fighter. I want to be a great fighter.”

As Herschel Walker and Julie Blanchard, his fiancée, jog through his Dallas neighborhood, Texas-size manifestations of ostentatious wealth loom everywhere. Vaquero is a gated enclave of spanking-new châteaus and palazzi, sculpted lawns and country-club amenities (a meandering golf course, jewel-like tennis courts, even stocked ponds with fishing poles at the ready). It has been home to celebrities (the Jonas brothers), major leaguers (the Texas Rangers’ Josh Hamilton) and CEOs too numerous to name. “You can order room service at your house,” says Walker, who a mile into the run speaks with the effortlessness of someone who could do this for hours. Indeed, it is only 7:30 on a summer morning, but he has been up since 5:30, already knocking out 2,000 sit-ups and 500 push-ups and then answering e-mails. As far as Walker is concerned, two and a half miles of roadwork before his business day starts is a form of cooling down.

In contrast to some of the larger estates on his street, Walker’s 7,300-square-foot, $2.5 million Mediterranean villa is relatively modest, but it is far beyond the budget of most of the fighters who train at the American Kickboxing Academy. “I’m a different kind of MMA guy,” he says matter-of-factly. “My life is different.” Walker’s stone driveway abuts a koi pond and fountain. Spanish arches grace the facade of his house. Inside there’s a wine cellar and a screening room. Upstairs a gym is under construction.

Walker has lived here for only several months. During the previous 10 years he was ensconced in a sleek downtown Dallas penthouse. But with Christian, his 12-year-old son by his marriage to ex-wife Cindy, approaching the age when a big yard seemed mandatory, it was time to move. “Christian is my little man,” he says.

Breakfast finds Walker and Blanchard, a dark-haired woman who is a vice president at CBS Outdoor Advertising, seated in Vaquero’s well-appointed clubhouse. Walker’s diet is more idiosyncratically Spartan than his idiosyncratically Spartan fitness routine. He eats only one meal a day, dinner, and is particular even then, limiting himself to lentil soup, salad, bread and an occasional chicken cutlet. He cheerfully admits to washing down Kit Kat bars with Coca-Cola. “Nutritionists say that’s bad for you,” Walker concedes but then demands, “If that’s so, why am I doing okay with it?” (Walker’s physique is so flawless that he appeared nude in ESPN The Magazine’s 2010 “Body” issue.) Still, he loves the ritual of dining. Even over an empty plate he relishes the give and play of online casino conversation between friends amid the clinking of glasses and silverware. After the waiter brings Blanchard her eggs and bacon and Walker a solitary glass of iced tea, he takes her hand and says a simple prayer: “Dear heavenly father, please bless this food that nourishes our lips, and bless our family.”

For all his ferocity in the MMA cage, Walker is an inherently sweet-natured, deeply religious homebody. He does not drink alcohol, and he does not curse. His idea of fun is to romp around his back porch with Christian and Cheerio, a golden retriever puppy that has the run of the place, or to plop down in front of any of his several televisions, all of which are permanently tuned to DVRed episodes of Judge Judy. A criminal justice major in college, he agrees with her no-nonsense verdicts and finds her acerbic worldview amusing.

Not that Walker allows himself much time for relaxation. Most days he is flying to New York, Las Vegas, Detroit or Fort Lauderdale. If he is in Dallas, he is tied up in endless rounds of conference calls. Although he made his first fortune in football, he has made a second one in the food business, and running it is an all-consuming affair. Walker launched Renaissance Man Food Services 12 years ago as “a little family concern” with just one offering—home-style chicken tenders prepared from his mother’s recipe. In the following decade he appeared at thousands of culinary trade shows across the country. “I always say to ex-athletes, ‘Guys, your name will get the door open, but unless you’ve got some substance you can’t get a seat.’ ”

Today Walker’s company consists of two divisions, including a recently purchased hospitality unit, and employs 300 people. Corporate offices are in Georgia. From three plants in Arkansas he distributes chicken sliders, chicken wings, chicken breast fajita strips and a host of other food items to clients that include the MGM Grand, Caesars Palace, the Hard Rock Cafe and McDonald’s. Last year his sales topped $80 million. “Somebody told me we’re the largest minority-owned chicken company in the United States,” he says, adding after a deadpan pause, “I don’t know if that means anything, as we may be the only minority-owned chicken company in the United States.”

Walker has achieved the dream of every famous jock, trading on his notoriety to create an enterprise that has paid for expensive toys (his 63-vehicle custom-car collection features a $250,000 Shelby KR) and should enable him to take care of himself and his family into perpetuity. He estimates his fortune at $25 million. If he wanted to he could coast from here on out. Yet Walker does not know how to coast.

“I think what people don’t realize is that we all have to get up and fight it every day,” he says during an afternoon lull in his schedule. “Life isn’t easy. Life is not easy. People think things ought to be given to you, but nothing is given to you. You gotta go out and earn it. Sometimes you gotta take it. Every day I get up and fight. Every day I’ve got to fight.”

Jerry Mungadze was in his office in the Dallas suburb of Bedford one evening several years ago when he picked up the phone and heard Herschel Walker say, “I’m in trouble.” A psychologist who specializes in post-traumatic stress disorder, Mungadze met the football legend in the building’s lobby. “Herschel was very distraught,” he says. “He was crying. He was in pain. He was hurting emotionally.”

Walker sought out Mungadze, whom he’d known casually since the 1980s, because a few days earlier he had armed himself with a handgun and driven to a meeting with the intention of killing a man whose sole offense had been to keep him waiting for the delivery of a custom automobile. According to Walker, an insistent voice inside his head said, “You don’t disrespect me. I’ve spent too much time with people disrespecting me.” He believes he would have committed murder had he not seen a smile, jesus loves you bumper sticker on the rear of his intended victim’s hauling van. The familiar maxim broke the spell. Still, he had come shockingly close to shooting someone—and not for the first time. On several occasions he had pointed a gun at his wife’s head, and more than once he had played Russian roulette. “I was on my way to prison,” he says, “or being dead.”

Mungadze met with Walker for weeks and arrived at a controversial diagnosis. Many psychologists believe that dissociative identity disorder, or DID, as it is better known, is not so much a bona fide condition as hysteria born of depression. This view holds that for every Sybil, the character suffering from a genuine split personality in the Sally Field film of the same name, there are thousands who contend with something less dramatic. But Mungadze was convinced that Walker had DID. “His was not one of the depressive syndromes. He was not clinically depressed.”

People close to Walker were incredulous. “I know him better than anybody,” his father told a reporter from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “because I raised him. This is my first knowing about that.” In an attempt to make light of the revelation, Vince Dooley, Walker’s college coach, said, “I like the personality he had when he ran the football.”

Initially Walker was also uncertain. Seeking a second opinion, he entered a California psychiatric hospital for three weeks as an outpatient. “For the first couple of days,” he recalls, “you say to yourself, ‘I’m not like these people here. I’m not like these people.’ Then, all of a sudden, it hit me. I was just like those people. The diagnosis was right—is right. That’s what it was. That’s what it is.”

As Walker came to understand, the source of his disorder could be traced to childhood. Although he grew up in a large, supportive churchgoing family in the rural Georgia town of Wrightsville, he had been a frightened boy (he was terrified, for instance, of entering his darkened home alone) who was dealt two of youth’s cruelest cards. “I was chubby, what my parents called big boned to keep from having to call me fat,” he says, “and I had a terrible speech impediment. I’d have to slap myself repeatedly on the arm just to get a word out.” By way of illustration, Walker takes a breath and with consonants catching on the back of his teeth mumbles, “I c-c-c-could not s-s-s-say w-w-what was on m-m-my mind.”

An overweight stutterer gripped by a resulting lack of self-esteem, Walker was, in his words, “a doofus” who in elementary school was so unpopular the only way he could get fellow students to talk with him at recess was by bribing them with his lunch money. Schoolmates called him Herschel the Girlshul. “By eighth grade I’d been beaten up 15 times,” he says. “On the last day of eighth grade I got beat up again. I went home and watched Gilligan’s Island and said, ‘That won’t happen to Herschel again.’ I was tired of it. I said, ‘Let’s do something about it.’ ”

In 1975, which he calls his “year of independence,” the 13-year-old Walker began forcing himself to stay up alone in the house at night and started reading books aloud in front of a mirror. “I read Cowboy Sam over and over to give me confidence,” he says. Walker also inaugurated his exercise program. Not only did he begin doing the thousands of sit-ups and push-ups that still sustain him, he started running barefoot along a lonely country railroad right-of-way and over a course his father plowed for him with a tractor in a field near their home. With the help of the high school football coach, he also invented a piece of brutal but effective training equipment. From an old harness, an oversize tire and a number of 10-pound shots, he built a weighted sled. After school, while his classmates wiled away their afternoons, he hitched himself to the sled and pulled it around the school track at top speed. “In eighth grade,” he says, “if anyone had asked if I’d be a good athlete, it would have been a big fat no with a laugh. By ninth grade I’d gone from a joke to one of the fastest kids in Georgia.”

Walker’s athletic feats at Johnson County High School are the stuff of legend. In his senior year he won state championships in the 100-yard dash and shot put and was the most highly recruited football player in America. But the triumphs, he says, came at an enormous cost. To survive the isolation that was his lot and the rigors of his singular pursuit, Walker developed an array of personalities that soon dominated his inner life. Some, like “the sentry,” were intended to ward off the taunts of schoolmates. Others, like “the enforcer,” were charged with punishing, at least in his fantasies, those who had done him wrong. “The hero” summoned him to ever greater gridiron achievements, while “the warrior” prepared him for combat with opponents. According to Walker, these alters, as therapists who treat dissociative disorders call them, were not just aspects of self but distinct characters with joys, needs, grievances and aspirations. Day in and day out he heard their clamoring voices.

For a long time it all somehow worked. As Walker writes in Breaking Free, his alters usually functioned in concert, transforming him into a veritable athletic superman. At the University of Georgia he overwhelmed huge linemen and sprinted past swift safeties. In his Heisman Trophy–winning year Walker averaged 159.3 yards rushing per game. Few could tackle him, and almost no one could catch him. “I think as a pure running back he’s the best there’s ever been,” says Dooley. “He had world-class speed, strength, toughness and discipline. He broke so many long runs for us. Even today he’s among the top 10 rushers in collegiate history. Most of the other guys in that group played four seasons. He played only three.”

Walker’s professional career also produced remarkable highlights. He is the only player in NFL history to have scored touchdowns in a single season on a run from scrimmage of 90 yards or more, a pass reception of 90 yards or more and a kickoff return of 90 yards or more. Because Walker spent his first years in the USFL, however, some of his greatest achievements—among them 2,411 yards rushing in 1985—go unacknowledged by the football establishment. Moreover, while he had spectacular seasons for both Dallas and the Philadelphia Eagles, he was not everyone’s idea of a classic NFL back. The pro game values finesse. Walker featured power. “Herschel was a bruising runner,” says Nate Newton, a retired Cowboys offensive lineman. “He wasn’t elusive. He didn’t have the shakes of an Emmitt Smith.” Then there was “the trade,” a still hotly debated deal that sent Walker from Dallas to the Minnesota Vikings in return for five players and six draft picks—an unheard-of ransom. The trade was supposed to turn Minnesota into an instant competitor, but due to internal squabbles, the Vikings underused Walker and went nowhere. The Cowboys, meanwhile, parlayed their influx of talent into the foundation of three Super Bowl championship teams. “The trade hurt Herschel,” says Michael Irvin. “But I say to him, ‘Look at what people think of you. Look at what they were willing to give up.’ ” Walker is satisfied to let his career numbers tell the final story. If record keepers took into account his combined USFL and NFL yardage—13,787—he would be the fifth leading rusher in pro history, ahead of Jim Brown, O.J. Simpson, Eric Dickerson and Ricky Williams.

In 1998, after returning to the Cowboys for his last two seasons, Walker retired. It was then that his dissociative disorder revealed its dark side. “Herschel really went through a hard time after retirement,” says Blanchard. Jerry Mungadze observes, “He began acting in ways inconsistent with who he thought he was, and it was devastating. He had personalities that had minds of their own. They felt differently, acted differently and used language differently.”

For Mungadze, Walker’s condition was anything but academic. “Once, he, his wife and I were in the office,” says the therapist, “and he threatened to kill her, myself and himself. I called 911, and the police came. That incident ended with him hitting the door and breaking his fist.”

Slowly, however, Walker made progress. “By resolving the traumas his alters resulted from,” says Mungadze, “the alters started listening to him and following his directions. I think he has now integrated his personalities and is a healthy guy.” The odds of Walker exploding in anger today, declares the psychologist, are “practically zero.”

“Only over the past couple of years have I been able to look at myself and say I love who I am,” says Walker, who is now such a believer in therapy that he has endorsed two mental-health outreach programs directed at people suffering not merely from dissociative disorders but from a full spectrum of emotional problems. Through Freedom Care, a division of Ascend Health Corporation, an operator of psychiatric hospitals, Walker speaks regularly to American armed forces members returning from combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. “I go to a lot of bases and say, ‘There’s no shame to admit you have a problem.’ ” Since 2009 the ex–NFL star has appeared at 31 military installations, helping initiate care for more than 6,000 troops. Walker’s other program, Breaking Free, is aimed at patients at Ascend facilities, where he helps lead weekly group therapy sessions. “What I’m trying to do,” he says, “is tell people there’s hope. There are people who’ve struggled so long they think there is no hope. But there is.” For Walker the programs offer an added benefit. “I get a lot of therapy by getting up and sharing and being brutally honest.”

Mungadze believes Walker’s entrance into MMA is the greatest evidence of his emotional well-being. Although the therapist says his patient’s warrior alter—“the one that supports him in his fighting”—is still active, he contends that Walker’s more troubling personalities have been silenced. If he were still hearing voices, Walker could not survive in the cage, where the very real threat presented by the fists, feet and knees of opponents would make such distractions deadly.

Walker’s love of MMA is unequivocal. The companionship of his fellow fighters at the American Kickboxing Academy and the attention he has received (his first two bouts aired live on Showtime and drew huge ratings) are gratifying. Even the money, whether he keeps it or not, is a form of respect. Promoters are dangling a $1 million payday for his third fight. “They’re making me an offer I can’t refuse,” Walker says. Most of all he relishes the competition. Since his teens, that is what has kept him sane. For Walker to thrive in the world, he must keep pushing himself to do things others regard as on the edge.

Those who care about Walker are now urging him to walk away from MMA. “We all feel scared,” says Blanchard. “His family does not approve. He’s done it. He’s proved it.” Walker hears them but says he will finish on his own terms. After this last fight, he says, “I can guarantee you there will be no more. It really won’t make sense for me to continue to fight after this year.”

Punk Carter’s Cutting Horse Ranch, 30 miles north of Dallas, is an unadulterated slice of old Texas. From its barn, bunkhouses and stables to its rustic ranch house, the place exudes Western authenticity. On a storm-threatened summer night, Herschel Walker has driven here to discuss an opportunity.

The proprietor, Punk Carter, spends most of his days teaching would-be cowboys how to ride and rope, but like a lot of country boys he is also a superb cook who augments his income with a line of spicy ranch hand ketchups and barbecue sauces. He and Walker are both in the food business. Along with a couple of partners they are developing a nutritional supplement, believing that a marketing campaign that capitalizes on Walker’s vaunted physique and his NFL and MMA pedigrees will get their product on store shelves. This evening potential investors have flown in from California.

As chicken and ribs sizzle on a grill, Walker, dressed in a TapouT T-shirt and faded jeans, strolls back to the barn, where Carter’s 14-year-old grandson, Brock, is performing rope tricks. Soon enough the boy has his famous visitor atop a mechanical device Carter devised to help instruct greenhorns. At the push of a button, a steer on wheels roars down a narrow-gauge track and the student tosses his lasso. After several tries, Walker gets the hang of it, and the boy graduates him to a more difficult task—bringing down a live calf. This job demands not only precise roping but also expert footwork. It is no easy thing to upend and control an animal that weighs 250 pounds. Again and again Walker tries. Again and again the calf breaks free. Eventually, however, Walker gets it right. With one leg wedged against the calf’s flank, he flips it over, ties its hooves and flashes a broad smile. He had come to Carter’s place to expand his culinary empire, but something entirely different is now on his mind.

“You know,” he says as he returns to the main house for his meeting, “a lot of the original cowboys were black. There’s no reason I can’t be a cowboy. I just might become a cowboy.” His grin suggests that while MMA may soon be behind him, he will still be game for just about anything. “To get greatness,” he says, “you’ve got to almost get crazy.”